Skin Protection During Radiotherapy: A Practical Guide for Hong Kong Patients

Skin prevention and care strategies for breast and head and neck cancer patients to reduce the risk of skin breakdown and ensure successful radiotherapy.

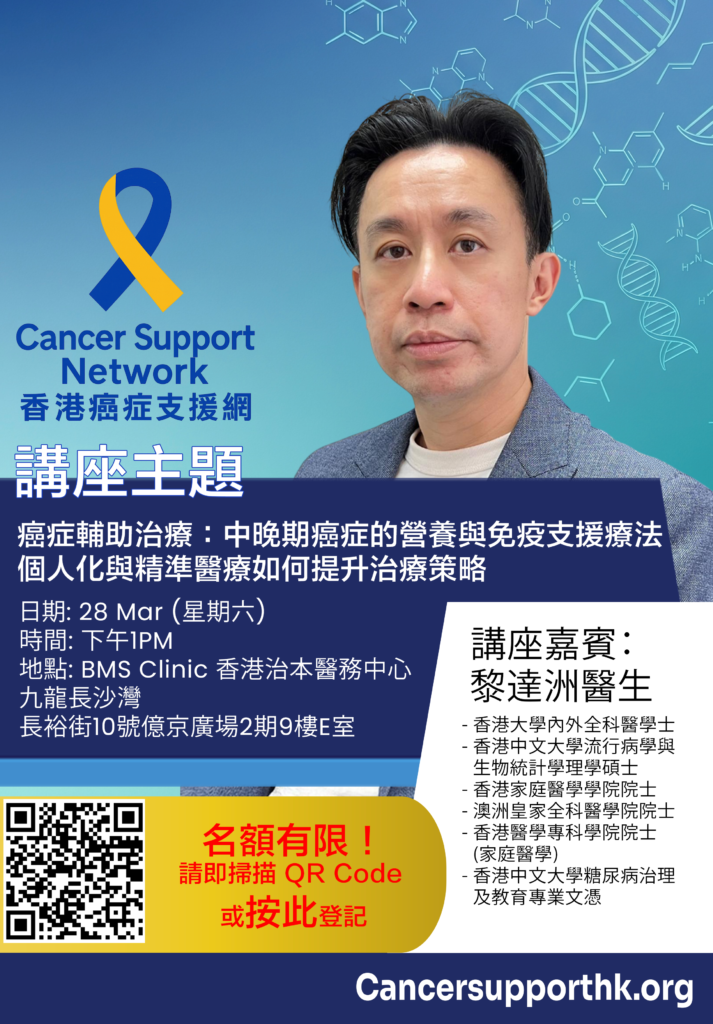

Free cancer support

In Hong Kong, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, and head and neck cancers are also relatively prevalent. Radiotherapy plays a critical role in the treatment of both.

For breast cancer, patients who undergo breast-conserving surgery followed by radiotherapy benefit not only from improved cosmetic outcomes but also from reduced local recurrence and better survival (Darby et al., 2011).

For head and neck cancers, radiotherapy—often combined with chemotherapy—significantly reduces recurrence and improves treatment success (Pignon et al., 2009).

One of the side effects patients worry most about is “skin burns” or “ulceration.” In reality, the vast majority experience only mild redness or dryness, and with proper skin care, severe reactions can be minimized (Hymes et al., 2006).

Introduction: The Role of Radiotherapy in Breast and Head & Neck Cancer

Why Does Radiotherapy Cause Skin Reactions?

Radiation primarily targets rapidly dividing cells, including both cancer cells and the basal layer of the skin (Ryan et al., 2013). When basal cells are damaged and cannot regenerate quickly enough, redness, dryness, or peeling may occur.

Skin reactions are commonly graded as follows (Porock, 2002):

- Grade 1: Mild redness, dryness, or slight peeling.

- Grade 2: Small areas of moist desquamation, often under the breast or armpits.

- Grade 3: Larger moist desquamation, with oozing or bleeding.

- Grade 4: Severe ulceration or necrosis, requiring specialist care.

Clinical studies show that over 90% of patients only experience Grade 1 reactions, rather than the severe “burns” some fear (Hymes et al., 2006).

Hong Kong Patient Perspective: Prevention Is Better Than Cure

In many Hong Kong oncology clinics, patients historically only received skincare advice after skin damage appeared. However, modern clinical guidelines stress the importance of preventive skin care—starting from day one of radiotherapy—to significantly lower the risk of severe dermatitis (Salvo et al., 2010).

Some patients worry that applying creams during treatment may interfere with radiation. Evidence shows that as long as the cream layer is thinner than 1 mm, it does not increase skin dose or reduce treatment effectiveness (Bolderston et al., 2006).

Skin Care Recommendations During Radiotherapy

Hong Kong patients can follow these practical guidelines:

1. Moisturize from Day One

Use fragrance-free lotions or gels containing ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or shea butter. Apply daily to maintain the skin barrier (Chan et al., 2019).

2. Avoid Friction and Pressure

Wear loose, cotton clothing. Avoid underwire bras or tight garments. Do not lie on rough surfaces or sleep facedown.

3. Use Advanced Radiotherapy Techniques

Many cancer centers in Hong Kong already use IMRT (Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy), which reduces skin dose and lowers the risk of severe dermatitis (Michalski et al., 2018).

4. Combine Medications with Skincare

- Preventive use of topical steroids (e.g., mometasone furoate) reduces the incidence of dermatitis (Boström et al., 2001).

- For moist desquamation, silver sulfadiazine cream can lower infection risk.

5. Support with Diet and Nutrition

A high-protein diet (fish, eggs, legumes) and vitamin C supplementation promote skin and mucosal repair (Arends et al., 2017).

Frequently Asked Questions (Hong Kong Context)

Q: Can I use regular moisturizers?

Q: Can I sunbathe during treatment?

✘ No, UV radiation worsens skin damage.

Q: What should I do if my skin breaks down?

Conclusion

Radiotherapy is essential in the treatment of breast and head & neck cancers, and skin reactions are the most common but largely preventable side effect. For Hong Kong patients, starting early with preventive moisturization, avoiding friction, leveraging advanced treatment techniques, and using medical support when needed can greatly reduce the risk of skin breakdown—allowing treatment to proceed smoothly and improving overall treatment success.

Contact our professional team now

References

- Arends, J., Bachmann, P., Baracos, V., Barthelemy, N., Bertz, H., Bozzetti, F., … & Preiser, J. C. (2017). ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clinical Nutrition, 36(1), 11-48.

- Bolderston, A., Lloyd, N. S., Wong, R. K. S., Holden, L., & Robb-Blenderman, L. (2006). The prevention and management of acute skin reactions related to radiation therapy: A systematic review and practice guideline. Supportive Care in Cancer, 14, 802–817.

- Boström, A., Lindman, H., Swartling, C., Berne, B., & Bergh, J. (2001). Potent corticosteroid cream (mometasone furoate) significantly reduces acute radiation dermatitis: A randomized study. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 59(3), 257–265.

- Chan, R. J., Larsen, E., Chan, P., & Blades, R. (2019). Prevention and treatment of acute radiation-induced skin reactions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer, 19, 1-11.

- Darby, S., McGale, P., Correa, C., Taylor, C., Arriagada, R., Clarke, M., … & Peto, R. (2011). Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women. The Lancet, 378(9804), 1707–1716.

- Hymes, S. R., Strom, E. A., & Fife, C. (2006). Radiation dermatitis: Clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 54(1), 28–46.

- Michalski, J. M., Gay, H., Jackson, A., Tucker, S. L., Deasy, J. O., & Mohan, R. (2018). Radiation dose–volume effects in radiation-induced rectal injury. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 76(3), S123-S129.

- Pignon, J. P., le Maître, A., Maillard, E., & Bourhis, J. (2009). Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): An update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 92(1), 4-14.

- Porock, D. (2002). Factors influencing the severity of radiation skin and oral mucosal reactions: Development of a conceptual framework. European Journal of Cancer Care, 11(1), 33–43.

- Ryan, J. L. (2013). Ionizing radiation: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 132(3), 985-993.

- Salvo, N., Barnes, E., van Draanen, J., Stacey, E., Mitera, G., Breen, D., … & Chow, E. (2010). Prophylaxis and management of acute radiation-induced skin reactions: A systematic review of the literature. Current Oncology, 17(4), 94–112.